Migration is generally considered to be positive for productivity and living standards. Motivated workers usually younger than the average of the native workforce boost the labour supply, increase productivity and support demand in the economy. In a study published last year the IMF concluded that migration – both high and low skilled – increase living standards. The study concluded that a 1% increase in the share of migrants in the population increases GDP per person in advanced economies by up to 2% in the long run. This increase comes primarily from a rise in labour productivity rather than a boost to the employment-population ratio. The case for highly skilled migrants boosting productivity is fairly clear cut – they bring diverse talents and expertise that may not be prevalent among the native labour force. But the low skilled case is rather more nuanced; two reasons are given for the beneficial effect on productivity of low skilled migrants; (i) they fill essential occupations for which natives are in short supply and allow natives to be employed at higher skilled jobs where they have a comparative advantage, (ii) by providing housekeeping and child care services low skilled migrants allow women to return to work or work longer hours.

UK population and labour force boosted by net migration

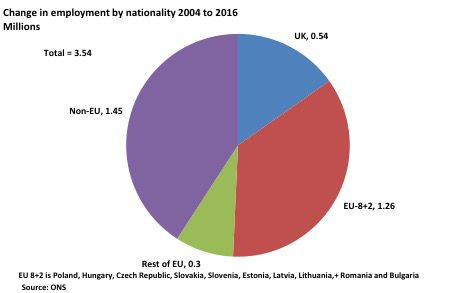

How does the UK’s recent experience fit with this conclusion? Over the last 13 years the population has increased by around 6 million 65.6 million. More than half of this increase 3.4 million was due to net migration, the vast majority of which entered the labour force. Indeed an overwhelming proportion of the rise in employment over the last 13 years has been from those not born in the UK – 3 million out of a total increase of 3.5 million. Of these 3 million just over half were EU citizens and 1 million of them were from the accession-8 – new EU members predominantly from Eastern Europe, including Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. This latter group were predominantly either unskilled or low skilled workers.

Growth of GDP per head has been anaemic

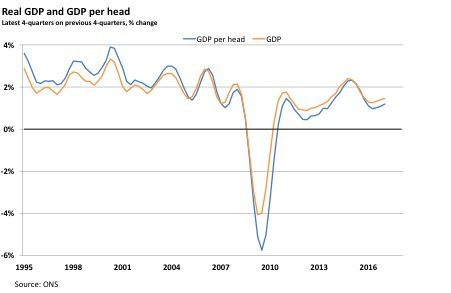

What is very clear is that the recent rise in migration has not been associated with an improvement in the rate of growth of GDP per head – rather the opposite. The chart below shows growth rates of GDP and GDP per head in real terms over the last 20 years. The striking feature is how, since the mid-2000s, GDP per head has grown more slowly than GDP – a reversal of the trend prior to the mid-2000s.

In the 10 years up to 2004 GDP per head grew on average by 2.7% a year, compared with 2.3% a year for GDP. But in subsequent years, real GDP per head growth slowed below GDP growth. After the Great Recession taking the period from 2010 until the first quarter of this year GDP per head has increased at an annual average rate of just 1% compared with 1.4% for GDP. In monetary terms GDP per head is estimated at £28,500 in 2013 prices in Q1 2017 – but if it had grown in line with GDP from 2010 onwards real GDP would by now be just over £30,000 a year.

A significant drop in the share of the population in employment could explain a slowdown in GDP growth per head. But this is not the case here as this share has been pretty steady in recent years. So the slowdown in GDP per head to below that for GDP itself is therefore a result of weaker productivity growth. This is the so-called “productivity puzzle” – the failure of productivity growth to recover to pre-recession levels as the economy returned to growth after the Great Recession of 2008/09. Output per worker increased at an annual average rate of 1.8% in the seven years up to 2007. But in the years since 2010 this average has slowed to just 0.7%. Various theories have been advanced to explain this including labour hoarding and “zombie” companies but firm evidence is elusive.

There is little to support the view that recent migration boosts GDP per head through increased productivity. The IMF argument for the benefits of low skilled migration finds even less support. True, such migrants often do jobs that the native work force is unwilling to do – seasonal agricultural work, care work, catering, cleaning etc. But there is scant evidence that such native workers do in fact redeploy to more value added jobs that make better use of their comparative advantage. Nor is there much sign of the so-called “nanny effect” – a boost to female participation rates. Latest data (three months to April 2017) record female participation (all those over 16 in the labour force) at 58.2%. This is up three percentage points since the start of 2004. But this appears to be the continuation of a long-term trend – in the 10 years prior to 2004 this rate increased by 2.5 percentage points.

A possible explanation for poor productivity performance is a change in the structure of the economy towards low skilled, low productivity occupations. One of the largest increases in employment in recent years – other than health and education – has been “accommodation and food services” a lower skilled industry. A supply of low skilled migrants may have filled these jobs since institutional factors e.g. the benefits system mean that native workers are reluctant to do them. Migration is associated with but not the cause of lower productivity growth. But a ready supply of low skilled labour paid at low rates may discourage firms from capital investment that would boost output per worker.

GDP per head more relevant than GDP – ask Japan

The media and analyst focus on economic growth – GDP – is understandable as it is the measure of all goods and services produced in an economy. But ultimately what matters are living standards – GDP or income per person. The UK’s performance here has been disappointing in recent years. In Japan GDP growth has been fairly weak over the last decade or more, but a declining population has meant that income per head has risen quite healthily and Japan performs well in international comparisons. In many respects the UK has the opposite problem – sluggish GDP per head growth with a migration boosted population and poor productivity

Migrants bring economic benefits to advanced economies IMF Blog 2016