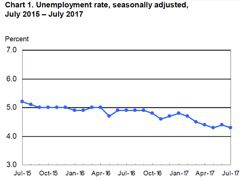

The US economy continues to expand steadily. Unemployment continues to fall, and the number of jobs has increased: the unemployment rate has fallen to 4.3 per cent from 4.4 per cent.

Strong employment growth

The monthly employment report for July was stronger than expected. Non-farm payroll employment rose by 209,000 more than the 180,000 figure expected by economists, and a larger monthly gain was recorded than the average: there was an 187,000 monthly increase in jobs recorded during 2016. After a slight overall upward revision to the data for May and June of 2,000, payrolls have increased at an average rate of 195,000 over the last three months. The length of the average work week for all employees was unchanged at 34.5 hours, and average hourly earnings went up for all employees by 9 cents: over the last year, average hourly earnings have risen by 2.5 per cent. The labour force participation rate rose slightly to 62.9 per cent from 62.8 per cent.

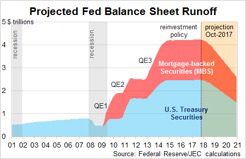

This increase in jobs in July is the eighty-second straight monthly increase in employment, which is the longest continuous increase in non-farm payrolls on record. This illustrates the sustained character of the present US recovery following the Great Recession, and the maturity of this economic expansion. While the pace of the recovery has been slower than previous expansions, its durability and length are clear. This suggests that the scope for a further stimulus to demand either from fiscal policy or monetary policy is limited. The rate of unemployment is significantly below the 4.7 per cent figure that the Federal Reserve considers to be the ‘natural rate of unemployment’. On this estimate, the American economy is at full employment and policy makers should be considering removing sources of stimulus from aggregate monetary demand, rather than looking to increase demand. Hence the message from the Federal Reserve Board last week about a tightening in policy led by the unwinding of its hugely expanded balance sheet.

Chart 3

The latest national accounts statistics underscore the continuing strength of the US economy. GDP expanded at an annualised rate of 2.6 per cent in the second quarter of 2017. And the surprisingly weak 1 per cent annualised increase in GDP in the first quarter was revised up to 1.2 per cent. The Bureau of Economic Analysis published its annual comprehensive revision to previous data, revising up its estimate of National Income and Product Accounts between 2014 and 2016 — the data on which GDP estimates are based. In 2014, growth was revised up by from 2.4 to 2.6 per cent, mainly as a result of higher recorded investment. In 2015, GDP was revised up from 2.6 to 2.9 per cent as a result of higher recorded consumer spending. While GDP growth in 2016 was revised down from 1.6 to 1.5 per cent, that was largely as a result of lower recorded exports.

An economy with little spare capacity

The upward revisions to the national accounts data and the continued expansion of employment suggest that the amount of spare capacity in the US economy is limited. The details of the GDP figures for the second quarter also suggest its continuing momentum. Investment increased by 5 per cent, adding 0.4 per cent to output.

It is difficult to argue with Federal Reserve officials, such as the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, that there is now little that the central bank or monetary policy can do to improve either growth or the functioning of the labour market. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Situation report for July illustrates some of the structural challenges that the US faces that are not tractable through monetary policy. Despite continued growth since 2009, the Labour Force Participation Rate, at 62.9 per cent, remains significantly below the rate before the Great Recession and the credit crunch in 2007, when it was 66 per cent. The labour force household survey shows that among different categories of major work groups, unemployment for teenagers at 13.4 percent, and for black people at 7.4, were about three and two times the rate for white people, which is at 3.8 per cent.

A labour market that is exhibiting structural problems beyond the influence of monetary policy

The roots of the US labour market’s contemporary problems are in micro-economic issues rather than a lack of overall aggregate demand that central bankers could help with. These micro-economic issues include the rules in the federal tax code that result in very high marginal tax rates, as tax credits, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and grants for college, phase in and out of the tax system; the high net rates of withdrawal that arise from the means testing of Medicaid and the subsidies paid through the Affordable Care Act; deficiencies in preparing school leavers for the work place; and the lack of effective active labour market policies to ensure that inactive people of working age remain attached to the labour market.